Oh to be back in the 19990’s and early 2000’s, when every technology was (mostly) viewed as apolitical and often as a force for good. Remember when connecting the world was seen as a universal good for the advancement of humanity? And then as the world wide web, mobile phones, social media, and other tech started to pervade all aspects of society, a few funny things happened. Tech entrepreneurs became billionaires, sometimes hundreds of times over. The politics of tech kept growing until it became just as or even more important than the tech itself. Social media algorithms were already surfacing as fundamental problems to be addressed. And then came LLMs and ChatGPT or “AI” as they’ve come to be known. For the remainder of this essay, “AI” will be shorthand for LLMS + GPTs. I see a direct lineage between social media and chatbots and even software coding agents – all of these technologies are designed to give humans dopamine hits such that they become addicted and come back for more. I don’t think this has been fully explored, and I want to point out the dangers of this pathway.

In a previous post, I posited that AI hysterics were dangerous and made a passing reference to the testosterone-dopamine pathway that was cited as one of the culprits of the great financial crisis. This is but one angle of critique. When it comes to AI safety and security, there are several vectors of criticism:

- Environmental cost (water, energy, mining, carbon, et al)

- Mass surveillance (facial and voice recognition, interconnected cameras, etc.)

- Racism (inadequate scrutiny of data sources, weights, etc.)

But I don’t think I’ve seen enough criticism of the psychological cost of “AI”, and this cost comes in a few forms:

- Reduced cognition and critical thinking

- Increased dependency on automation

- Shifting of risk outcomes (I’ll explain this one in more detail)

- AI mania and even psychosis

I’ll go through each of these, but first I’d like to do a little context setting.

AI and the Attention Economy

Most of us forget that the fundamentals of what we call AI came from 2 sources: big data analytics and social media. With the ability to process large amounts of data came the ability to create recommendation engines, to do “sentiment analysis”, and to create ways that kept people engaged so that the Facebooks and Googles of the world could create evermore ways to print money. Those friend recommendations you get from Facebook and LinkedIn? Big data algorithms. The prioritized links in Google? Big data algorithms. Product recommendations from Amazon? You guessed it! Big data algorithms. For the last 20 years, a large segment of the technology industry has been focused on keeping people engaged and winning the “attention economy”. Such tech has been called “brain crack” that leads us down cognitive pathways we would not have otherwise gone down, feeding an addiction to social media to the point where people lose touch with reality and forget how to “touch grass”. Thus, it was inevitable that the industry would land on the ultimate addictive technology: LLMs, at first embodied by ChatGPT. These tools are geared to reinforce prior beliefs, inflating an individual’s sense of self and becoming positive feedback loops for whatever an individual was feeling at the time. This is why using them for therapy has been so disastrous. A bot designed to keep you coming back for more cannot be trusted to tell you what you need to hear as opposed to what you want to hear. Using these tools produces a dopamine high, even more than what participants feel through social media.

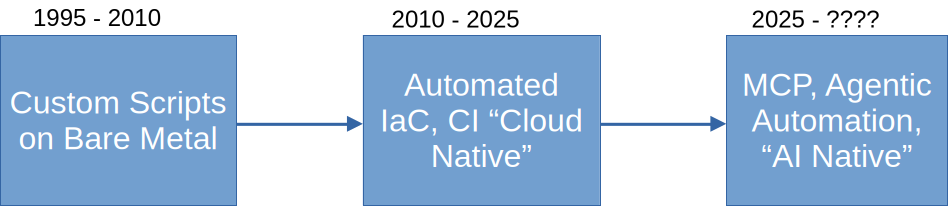

But the effects are not just limited to personal chats. It extends to productivity applications as well. Consider writing code. The promise of AI in its agentic productivity form is that it will automate all of your tasks. And in truth, these have proved to be highly valuable tools: witness the breathless hysteria that follows every new release of Anthropic’s Claude Code or OpenAI’s Codex. But I want to point out that just as with a hammer, all the world looks like a nail, so too does agentic engineering make all the world look like a software problem. And yet problems persist: Coding agents were shown to give developers the illusion of productivity. And apparently, 95% of agentic engineering initiatives fail to live up to their promised outcomes. AI is showing us in real time that coding was never that valuable to begin with, a point I made 6 years ago in the context of the 10x engineer. I’m not arguing against the potential power and impact of these tools. What I’m arguing is that the dopamine addiction that accompanies AI chat usage is just as powerful and addictive in productivity tools. In fact, it may be worse because technology practitioners tend to view their tools as non-political and devoid of cultural context.

To critically and fully evaluate the promise of these tools, we have to be able to look at outcomes objectively, divorced from the dopamine hit that comes from an initial high when you achieve a result so much more quickly than before. We also have to consider the possibility that perhaps behind forced to go slow, because doing these things was hard, prevented us from making stupid mistakes and gave us time to be more thoughtful. Consider the possibility that going slower was a feature, not a bug, but more on that later.

The Limits of Automation

There’s a very famous disaster that I like to point to when referring to the dangers of automation: Air France flight 447. There’s a lot that failed mechanically on that flight, but one thing that was very clear: when the plane dropped out of autopilot and handed the controls back to the pilots, they made very poor decisions. Automation is great. Everyone loves automation because everyone loves the idea of removing tedium from their daily lives: work, personal, and otherwise. So automation is great – until it isn’t. There is a very real concern that outsourcing more of the cognitive load will reduce your brain’s ability to think critically when needed the most – such as when the automation breaks and you will need to solve the problem yourself. High school and college educators, already concerned by the drop in cognitive ability brought about by social media and doom scrolling, are sounding alarm bells about “zombie” students addicted to ChatGPT and the like.

This brings us to an interesting – and concerning – paradox: as we are able to outsource and offload more and more cognitive tasks, do we accomplish less because we lose the ability to actively solve problems as we lose connection and ownership of outcomes? Have we already reached that point? These tools are very very good at producing competent products, whether long-form summaries, software, or tech services, or at least the appearance of competence. But what happens when we are unable to critically analyze the outcomes of the decisions we’ve outsourced to these tools? I get the sense that we’re about to find out shortly. The counter argument to all this is that these tools hand individuals more ability to think creatively, removing the drudgery and freeing our minds to focus on the more rewarding parts of our jobs. This seems plausible, but I think there are limits. In a recent Galaxy Brain podcast, Anil Dash compared and contrasted the impacts of AI on coding with that on writing and art. AI-assisted coding, according to Dash, was free of drudgery and allowed more creative expressions, whereas AI-assisted writing and art turned the creator into an editor. In other words, AI-assisted art was all drudgery no lift, whereas AI-assisted coding was a liberating experience.

Side Note: I expect this is true up to a point. For now, we’re only seeing the positive aspects of agentic engineering because we haven’t yet fully gone down the path of “engineering management” which is where this appears to be going. Will engineers really be singing the praises of AI when they realize they’re just middle management now? They still won’t have any real agency, but they’ll own the end product. But I digress…

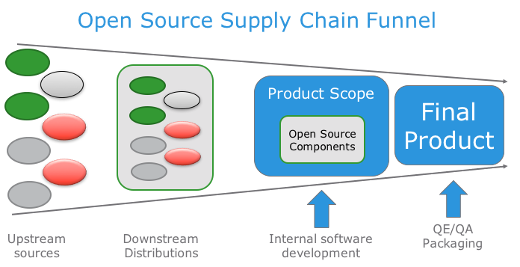

But the question remains: if we agree that these tools are essentially purpose-built to form positive feedback reward engines for their users, where is the critical thinking for preventing mistakes going to take place? And I don’t mean mistakes like typographical or syntax errors. I mean things like enabling mass surveillance of particular races or ethnicities. Or creating financial services applications that reward and punish entire segments of populations. When we outsource so much of the cognitive load in these circumstances, how will we know when things are gone awry? These are not simply “bugs” that a code linter will catch. These are fundamental errors that will be expedited by our brave new agentic world, and we can’t guarantee that our practitioners or “agent managers” will have the know-how to prevent these outcomes or even detect them after release. The more cynical among us would argue that this is the point and the system is working as designed. I’m still holding out hope that the vast majority of people don’t actually want to be racist assholes.

Outsourcing more of the cognitive load will lead us to pay less attention to what is happening and have less understanding of these systems in general. This does not bode well when an increasing amount of our decisions will be agentic, from sources that are designed to maximize and reward our prior biases. Positive feedback loops are real. Confirmation bias is real. How do we prepare for a future where we’ve automated our mistakes and make them difficult to detect? The AI maximalist would argue that we create agents to challenge decisions from other agents. I can definitely see that future unfolding before our very eyes, and I’m going to express great skepticism as to its ultimate effectiveness. This sentiment was expressed well by Jasmine Sun in her essay “Claude Code Psychosis“. In it, she walked through her experience with Claude Code, noting its power and her new ability to create things that were previously not possible for her. But she also came to another realization: its use is primarily for “software-shaped problems” which, it turns out, are not actually the majority of problems we’re presented with in life. But that won’t stop your typical, self-described “10x engineer” from thinking in those terms. The more sophisticated these automation tools become, the more we anthropomorphize them, and the more we trust them with decision-making capability, which is not what they were created to do.

Shifting of Risk

What this means in real world terms is that we have to think about risk differently. It used to be that risk was something that could be quantified according to the quality of output and competence. Incompetent workers produced brittle, poorly performing products that would easily break and cause damage. Competent workers produced higher quality work that broke down less. Manufacturers like Toyota, which became famous for its mantra of continuous improvement, created systems and processes based on the notion of rewarding competence and preventing substandard work from being released to the public. And that is largely how we thought about systems and outcomes: did it break? Did it perform well? What could have been improved? And then loop that feedback into the system and make the next release incrementally better.

But what happens when the question of competence goes away, and the quality of a given product is no longer a concern? Do we assume it went well because it didn’t break? In the past, the assumption is that because humans were in control of decision-making, the risk of malformed products would be addressed upfront, before engineers ever got to work creating a product. In that world, there were many links in the chain that required human intervention where someone could point out fundamental problems before they went too far down the release path. We can all think of incidents where a product release became its own momentum and disaster resulted because no one was empowered to speak up. Now think about agentic systems with even fewer pauses in production and break points managed by humans. At what point do we realize that making things go faster will have the unintended side affect of allowing management’s mistakes to be unleashed on the world before anyone can stop it?

There is a case to be made that intentionally slowing down production could actually be beneficial. One of my favorite TV series is “The Pitt”. (streaming now on HBO Max!!!) In a recent episode, one of the characters could be heard uttering the phrase “slow is smooth, smooth is fast.” I was intrigued by that line and discovered that it originated from the Navy Seals. In the context of the show, this line was used to ensure that doctors were taking the time to do what is best for patients. Incidentally, The Pitt also has an interesting, nuanced take on the use of AI for productivity. Taking that line of thought to its logical end, we can intentionally gives ourselves more checkpoints to evaluate risk, and not just in terms of the quality of what is being released, but to evaluate the potential outcomes that will be the result.

AI Mania and Even Psychosis

Most of what I’ve written above has been included in a number of other meta analyses of AI in productivity tools. But the part that concerns me the most, even more than everything else above, is the affect that these tools have on the practitioners that use them, and I don’t just mean on cognitive abilities. Let’s talk about addiction. Let’s talk about mania. And let’s talk about how this affects our decision-making abilities. When you combine cognitive outsourcing, dopamine highs, and reduced critical thinking, things can go awry quickly. Ever since ChatGPT exploded on the scene in 2022, there has been a steady drumbeat of exaggerated claims of the capabilities of these models and agents, both pro and con. On the hype side, you have any number of AI company executives and tech futurists touting how we are on the brink of artificial general intelligence (AGI) and entering a new era of humanity, one with lots of leisure time because all the drudgery of labor will be done by machines, giving us more time to do… something something fulfillment and enlightenment. Ironically, those casting warnings of impending doom from AGI tout the technology in exactly the same terms. Except in their examples, the power of AGI is turned against us once the machines become sentient and decide that humans are surplus to goods.

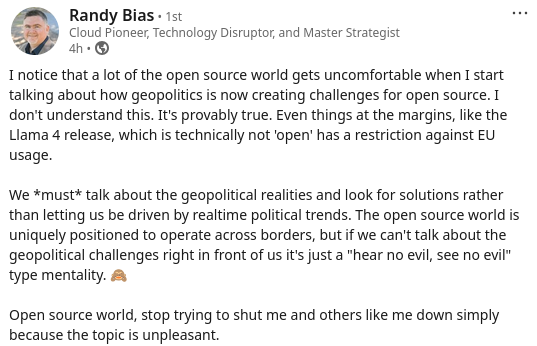

Let’s be frank: these tools are powerful, and they are reshaping the tech industry at great speed. But I fear for the psychological impact that they seem to have on my tech brethren (and it is mostly brethren). I have a colleague who has described his recent foray down the path of agentic entineering in terms of lost sleep, increased anxiety, and his inability to relax. This is not a good outcome. Just as with social media and our children, I am growing increasingly concerned that using these tools breaks our brains. Tech people are in the habit of making fun of anti-vaxxers and other anti-science people, and the connections between those movements and social media are well established. What if we discover that we tech people, who love to pride ourselves on our ability to think rationally, are just as susceptible to the same kinds of incentives and rewards feedback loops that send our drunk uncle down conspiracy theory rabbit holes? And what if we discover that these agentic-induced manic episodes turn out to be just as dangerous, if not more, than those triggered by social media engagement algorithms? It could be that these are even more dangerous because we don’t expect productivity tools to be dangerous, and we don’t view their outputs as critically, especially not when we’re high on dopamine.

Speaking of dopamine… there is a large body of evidence that links testosterone levels, cortisol, and dopamine to risk-taking behavior. There’s an interesting common thread in the above narratives: the overwhelming majority are from men. This testosterone-dopamine pathway has been linked to the high risks taken by wall street traders and their consequences: the great financial crisis of 2008. The basic – and probably oversimplified version – is this: when we are rewarded for taking risks, we get a hit of dopamine which is a pleasurable experience. Testosterone can increase or induce the release of dopamine, which means that for those with higher levels of testosterone, the release of dopamine will also be higher, meaning that the pleasure centers of our brain get more excited when we are rewarded for risk taking. Much of the research I’ve seen online has been in the context of financial decisions and the links to the great financial crisis. But when I read the descriptions by wall street traders of the mania they would experience, it starts to sound awfully familiar to the type of mania I’ve heard described by AI practitioners. The need for less sleep. The feeling of additional energy and that nothing can touch you in these moments – that during these manic episodes they feel as though every decision they make and every idea they have is spectacular and world-changing. All of this is starting to sound very familiar. And when surrounded by tools that give you feedback almost instantaneously, that feeling of mania can be induced quickly, potentially causing the practitioner to develop an addiction.

This effect, which I’ll call AI Brain, would explain a lot. It would explain why the most hysterical proclamations are from men. It would explain why we get breathless accounts of amazing productivity, without very much real world impact. It would explain the study by METR on the “productivity illusion” of using AI coding tools. It would explain the MIT study that showed that 95% of AI initiatives in the enterprise failed. it would also explain the cognitive dissonance between the proclaimed advantages of using these tools and the actual real-world results. Lots of people are loudly saying that everyone needs to get onboard, but so far what I’ve seen is just more tools for creating other agentic tools. Taking a step back, it’s agents all the way down. To put it bluntly, I’ve yet to see a cure for cancer. Detection rates based on radiology images have not changed. Neither has surgical outcomes. Nor quality of artworks. Nor world-changing fiction. And not even replacements for our most used software tools. I suspect what will happen is that AI tools will become intrinsic in the production of all of those things, but as we’ve already seen, much is yet to be done to ensure reliability, resilience, and safety. In short, agentic tools do not help solving the human-shaped problems we’re confronted with, even if we are focusing on the software industry itself.

So What Do We Do?

The intent of this essay is not to disclaim the power of agentic tools. They are of course quite powerful. But we all remember the lessons from Spiderman, right? With great power comes great responsibility. We are going to have to rethink our approach to automation and really engineering in general. We are going to have to figure out how to insert checkpoints into our processes, because we can no longer take for granted that they will exist.

I think the best way to think of this comes from Anil Dash in the above-referenced Galaxy Brain podcast:

Okay, think about what could a good LLM be. “I want it to be environmentally responsible. I want it to have been trained on data with consent. I want it to be open source and open weight, so that technical experts I trust have evaluated how it runs. I want it to be responsible in its labor practices. Want it to—” Come up with a list, right? So there’s, like, four or five things. And if I can check all those boxes, then I could feel responsible about using it in moderation. And it’s only implemented in apps that I choose to have it in—not forced, like the Google thing where it jumps in front of my cursor every time I start trying to type or whatever. Like, that could be useful. And then I would feel like I was engaging with it on my own terms. That doesn’t feel like science fiction. That feels possible.

These tools are powerful, and they can have a positive human impact, if we choose to use them in that way. We don’t have to accept the inevitability narrative of “something big is happening” and “all your jobs are going away!!!” Denying the use of these tools is not the answer. Finding ways to prevent harm is the path forward.

I think we’ll find out that AI Brain is real, and it will be incumbent on us, the practitioners, to provide the critical view necessary to ensure that we don’t lose a generation to a dangerous positive feedback loop. Over the last decade, we’ve seen where that leads – fascism, anti-science, and polarization. Let’s not repeat our mistakes and make the problem worse.